Edited May 15, 2025:

Parnassus (in New Kensington, PA) shares a historical figure with downtown Columbus, Ohio. In fact, this story even left its mark on Columbus’ current National Hockey League arena.

I discovered this from an episode of Haunted Talks – The Official Podcast of the Haunted Walk, hosted by Creative Director Jim Dean. In Episode 68 – Columbus Ghost Tours, the host interviewed the Columbus tour co-owner Bucky Cutright.

Cutright shared one ghost story from his tour – the tale of “haunted” Nationwide Arena, the home of the Columbus Blue Jackets, an NHL team. Cutright revealed that the arena was built on the parking lot for the former Ohio Penitentiary.

Cutright noted that an indigenous Mingo village (Salt-Lick Town) once stood on this entire property. He talked about the village’s destruction in 1774. He described the death toll of Mingo families, at the hands of white settlers led by a man named William Crawford.

(My knowledge of the incident in question is limited to the interpretation of this referenced tour guide operator. I have no knowledge of the tour operator’s research methods.)

“Wait a minute,” I thought. “Our William Crawford?“

See, I live in the Parnassus neighborhood in New Kensington, Pennsylvania. Parnassus emerged from the remains of Fort Crawford, at the confluence of Pucketa Creek and the Allegheny River.

Colonel William Crawford’s troops in the Continental Army built Fort Crawford in 1777. This was during the American Revolutionary War. Crawford previously fought with the British in the French and Indian War in the 1750’s. Crawford survived the Battle of the Monongahela (Braddock’s Defeat) in 1755. Crawford knew George Washington!

I Googled “William Crawford” and “Columbus.” I saw the portrait of the man who led the expedition on Salt-Lick Town in present-day Columbus. This was indeed “our” William Crawford!

Now, to be clear, I do realize that William Crawford doesn’t “belong” to New Kensington. Crawford was born in Virginia. Connellsville, PA, reconstructed his Pennsylvania log cabin. Crawford County, PA, was named after William Crawford. Crawford County, OH, was also named after William Crawford.

To clarify: Colonel Crawford was involved with multiple controversies. His legacy has now extended to lore and historical fiction. See my above note that he is now apparently the subject of a tale in a ghost story tour in Columbus, Ohio. He also appears in a historical fiction novel that I reference later in this blog post.

For instance, Crawford was involved in Lord Dunmore’s War. The Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh has an exhibit about this.

During this time period, Simon Girty, a white guide who was raised by Native Americans, defected to the British and their Native American allies. Prior to the defection, Girty operated out of Fort Pitt as a “home base.” Girty’s defection to the British was a controversial event in Western Pennsylvania. Girty fled to Ohio. The Heinz History Center provides excellent resources on Simon Girty.

In 1782, Crawford led the Crawford Expedition against Native American villages along the Sandusky River in Ohio. These Native Americans and their British allies in Detroit found out about the expedition. They ambushed Crawford and his men. These Native Americans and the British troops defeated Crawford and his militiamen.

A force of Lenape and Wyandot warriors captured Crawford. They tortured Crawford. They executed him by burning him on June 11, 1782.

Simon Girty was there, at William Crawford’s execution.

Girty settled in Detroit, among the British. Years later, Detroit became part of the United States and Girty fled to Canada.

Agnes Sligh Turnbull (a native of New Alexandria PA and a graduate of IUP) later wrote the historical fiction novel “The Day Must Dawn.” William Crawford and Simon Girty appear together in this novel.

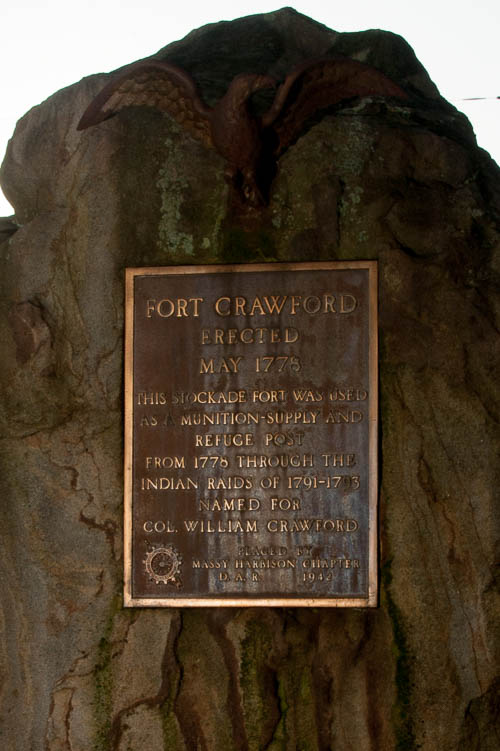

Per the photo at the top of this blog post, there is a monument to Fort Crawford and to Colonel William Crawford in Parnassus in New Kensington. The Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated it in 1943.