Jonathan and I live in a house built in the 1890’s.

The Alter family originally owned our home. This same family is now buried in a churchyard down the street.

Jonathan researched the Alter family.

Let’s start with the family patriarch, Frank Alter Sr.

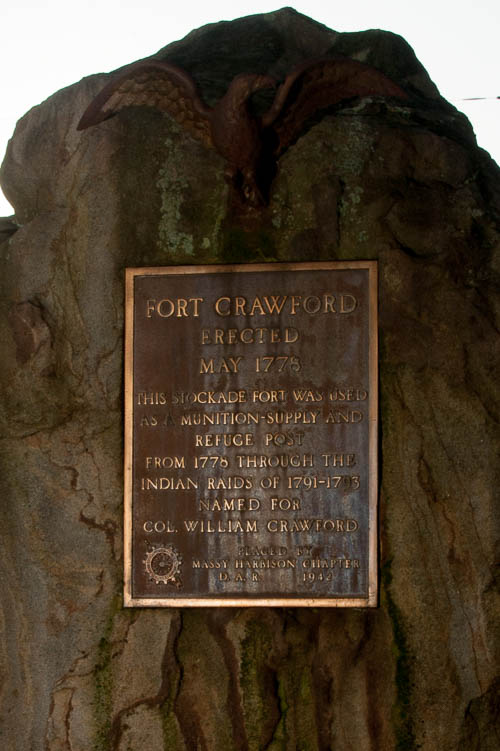

Alter was born in 1871 in Pittsburgh.

Alter’s father fought in the Civil War. Alter’s father then maintained a long career with the Allegheny Valley Railroad Company.

Frank Alter Sr.’s own professional life began at age 17 with his own job at the Allegheny Valley Railroad Company as a telegraph operator. Four years later, he was appointed station agent at New Kensington.

Now, shortly after Alter assumed his first job with the railroad, the Johnstown Flood killed over 2,000 people, in May 1889. A privately-owned dam on a private lake upstream from Johnstown failed. The wall of water demolished the communities that sat between the lake and Johnstown, and then the water hit Johnstown and destroyed it as well.

The flood occurred upstream from New Kensington. It occurred on a tributary to a tributary of the Allegheny River. According to the book “The Johnstown Flood” by David McCullough, flood debris washed downstream from Johnstown, eventually into the Allegheny River, on to Pittsburgh and points beyond. McCullough wrote that somebody plucked a live baby out of the Allegheny River in Verona, which is downstream from New Kensington. McCullough wrote that onlookers stood on the banks of the Allegheny, watching the results of the flood flow past them. Some even plucked souvenirs from the river.

Did Alter first learn about the flood during his duties in the telegraph office? Did he join the crowds which lined the Allegheny River’s banks?

Now, I grew up an hour’s drive south of Johnstown, and my sixth grade class studied the Johnstown Flood. We read excerpts from McCullough’s book.

McCullough acknowledged at the beginning of his book that “most” of the dialogue in Chapters 3 and 4 of his book had been taken directly from a transcription of testimony taken by the Pennsylvania Railroad in the summer of 1889. The railroad’s tracks lined the tributaries hit hardest by the flood. The railroad’s telegraph system documented events leading to the moments before the flood wiped out the tracks and the telegraph lines.

McCullough’s book noted that in the moments before the Johnstown flood happened, a railroad telegraph agent communicated the impending dam failure to Hettie Ogle, who ran the “switchboard and Western Union office” in Johnstown.

McCullough identified Ogle as a Civil War widow who had worked for Western Union for 28 years. The book noted that she was with her daughter Minnie at the time. She passed the message on to her Pittsburgh office. McCullough noted that the two perished in the flood and their bodies were not recovered.

When I was in the sixth grade, I was told that Hettie Ogle faithfully stayed at her telegraph post and relayed river gauge data until at last she wrote:

THIS IS MY LAST MESSAGE

The story haunted me.

Based on how this story was presented to our class, I was under the impression that Hettie Ogle was trapped in the telegraph office with just her daughter. I assumed that Hettie Ogle and her daughter were “rare” because they were women who also worked outside the home at the telegraph office.

Now, here is something that McCullough’s book did NOT tell me, and that I learned instead from the website for the Johnstown Area Heritage Association (JAHA): Ogle was actually trapped in that office with her daughter Minnie, “four other young ladies” who were named by the JAHA website, and also two named men. When I read the website, I understood this to mean that all eight of the named women and men who were trapped in this telegraph office worked in the telegraph industry. They all perished.

I didn’t realize until I first read the JAHA website that Hettie Ogle actually managed an office full of staff. I also didn’t realize that many of the employees in Johnstown’s Western Union office in May 1889 were women.

I have since figured out that if Hettie Ogle worked for Western Union for 28 years until she died in 1889, that means that she started her Western Union career in 1861. The Civil War also started in 1861. As I noted above, she was identified as a war widow. Did she have to take a job with Western Union in order to support her children when her husband went off to war? Did she do it out of a sense of duty for the war effort, and then she stayed with it because she enjoyed the work? What circumstances led her to her “duty” operating the telegraph?

I speculate that since Frank Alter Sr. got his start in the railroad industry as a telegraph operator, the tragedies of the Johnstown Flood would have impacted him personally. Perhaps he even knew some of the telegraph and / or railroad employees who died that day in 1889.

The telegraph industry of the 1800’s fascinates me because I think a great deal about my own dependence on technology.

I first realized how much I – or at least my sense of well-being – depended on being able to keep contact with others and with information on September 11, 2001. I lived in the family home in Somerset County. I worked in downtown Johnstown. Flight 93 crashed between these two points while I was at work that day.

After I and my co-workers watched the twin towers burn live on television, our employer’s co-owner told us to “go back to work.”

However, a few minutes later, this same co-owner’s daughter rushed through the office to announce that a plane had crashed in Somerset County. (This plane, we later learned, was Flight 93.) We learned that we – along with every other worker in downtown Johnstown at that time – were being evacuated because a federal court building existed in downtown Johnstown. I couldn’t reach my family who lived with me in Somerset County on the phone. I attempted, and I had no connection. I then learned that we were being asked to stay off of our phones in order to leave the lines available for emergency crews. I also learned that a portion of Route 219 – the main highway that I used to drive to my family home in Somerset County – was closed due to the morning’s events. I was being forced to leave downtown Johnstown due to the mandatory evacuation, but I had no information about whether I would be able to get back to my home in Somerset County.

I made it home to Somerset County without incident. However, this was the first time that I remember feeling confused because all of my decision making instincts depended on information that I couldn’t access.

More recently, I thought that I was so slick because I specifically curated my Twitter feed to follow the feeds for Pittsburgh’s transit agency, the National Weather Service, and several other emergency management agencies. I worked in downtown Pittsburgh by then, and I commuted home each weeknight – usually by bus – to New Kensington. I reasoned that with my specially curated Twitter feed, I would have available all of the information that I needed to make informed decisions about my commute home if I were to be in Pittsburgh and a natural disaster – or another terrorist attack – happened.

However, on the day that Pittsburgh and its surrounding region had a major flash flooding event, Twitter broke. I had based my entire theoretical emergency plan on having up-to-the date tweets from all of the sources that I listed above. I had access to no updated information from any of these sources.

Once again, I felt completely betrayed by technology at the moment when I felt its need the most.

Now, for another story that I have about being dependent on technology:

I read part of “The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant).” Julia Dent Grant (JDG) was born in 1826. In 1844, Samuel Morse sent the United State’s first telegram over a wire from Washington to Baltimore. (Congress partially funded this.) In 1845, JDG’s father, Frederick Dent, travelled from their home in St. Louis to Washington for business. He sent a telegram to Baltimore. JDG wrote that her father received an answer within an hour and that “it savored of magic.” The event was such a big deal that Frederick Dent brought the telegraph repeater tape back home to St. Louis to show the family.

Now I’m going to skip ahead in the memoirs to 1851. At this point in the memoirs, JDG is married to Ulysses S. Grant and they have an infant son. Julia visited family in St. Louis while her husband was stationed at Sackets Harbor, near Watertown, in New York State. JDG planned to telegraph her husband from St. Louis, and then travel with her nurse to Detroit. Then, she would release her nurse and meet her husband in Detroit. Finally, she would travel with her husband from Detroit to Sackets Harbor. I am under the impression that the trip from St. Louis to Detroit to Watertown was all by train.

Well, JDG telegraphed her husband in St. Louis per the plan. She left St. Louis and travelled with her nurse to Detroit. She dismissed her nurse and waited for her husband in Detroit. Her husband never showed up. JDG eventually travelled alone with her baby to Buffalo, hoping to meet her husband there. Her husband wasn’t in Buffalo, so she continued on the train to Watertown. From Watertown, she had to hire a carriage (the Uber of the 1800’s), and travel to Madison Barracks, the military installation at Sackets Harbor. The entrance to Madison Barracks was closed, so she had to yell to get a sentry’s attention.

The telegram that JDG sent to her husband from St. Louis arrived at Sackets Harbor IN THE NEXT DAY’S MAIL.

That’s right – at some point in the journey, the telegram failed to perform its basic function as a telegram. The telegram became snail mail.

After JDG’s husband was promoted during the Civil War, he travelled with his very own personal telegraph operator. (In fact, the Grants learned about President Lincoln’s assassination through a personal telegram received by the personal telegraph operator.)

By the end of the Civl War, the Grants had come a long way since their days of “snail-mail telegrams.”

Other people have actually written entire books about how telegraphs and semaphores affected the Civl War.

Here’s one of my favorite parts of JDG’s memoirs: At one point during the war, JDG asked her father, Frederick Dent, why the country didn’t “make a new Constitution since this is such an enigma – one to suit the times, you know. It is so different now. We have steamers, railroads, telegraphs, etc.“

I just find this so fascinating because JDG witnessed her country’s tremendous changes that resulted from Technology. She wondered how all of these Technology changes affected her country.

I, personally, spend a lot of time wondering about how Communication Technology in general – the telegraph, the internet, whatever – changed our national culture and also changed each of us as people.