Edited February 1, 2022:

I just learned that Parnassus (in New Kensington, PA) shares a historical figure with downtown Columbus, Ohio. In fact, this story even left its mark on Columbus’ current National Hockey League arena.

I discovered this from an episode of Haunted Talks – The Official Podcast of the Haunted Walk, hosted by Creative Director Jim Dean. In Episode 68 – Columbus Ghost Tours, the host interviewed the Columbus tour co-owner Bucky Cutright.

Cutright shared one ghost story from his tour – the tale of “haunted” Nationwide Arena, the home of the Columbus Blue Jackets, an NHL team. Cutright revealed that the arena was built on the parking lot for the former Ohio Penitentiary.

Cutright noted that an indigenous Mingo village (Salt-Lick Town) once stood on this entire property. He talked about the village’s destruction in 1774. He described the death toll of Mingo families, at the hands of white settlers led by a man named William Crawford.

(My knowledge of the incident in question is limited to the interpretation of this referenced tour guide operator. I have no knowledge of the tour operator’s research methods.)

“Wait a minute,” I thought. “Our William Crawford?“

See, I live in the Parnassus neighborhood in New Kensington, Pennsylvania. Parnassus emerged from the remains of Fort Crawford, at the confluence of Pucketa Creek and the Allegheny River.

Colonel William Crawford’s troops in the Continental Army built Fort Crawford in 1777. This was during the American Revolutionary War. Crawford previously fought with the British in the French and Indian War in the 1750’s. Crawford survived the Battle of the Monongahela (Braddock’s Defeat) in 1755. Crawford knew George Washington!

I Googled “William Crawford” and “Columbus.” I saw the portrait of the man who led the expedition on Salt-Lick Town in present-day Columbus. This was indeed “our” William Crawford!

Now, to be clear, I do realize that William Crawford doesn’t “belong” to New Kensington. Crawford was born in Virginia. Connellsville, PA, reconstructed his Pennsylvania log cabin. Crawford County, PA, was named after William Crawford. Crawford County, OH, was also named after William Crawford.

(Edited February 1, 2023 to clarify: Colonel Crawford was involved with multiple controversies. His legacy has now extended to lore and historical fiction. See my above note that he is now apparently the subject of a tale in a ghost story tour in Colunbus, Ohio. He also appears in a historical fiction novel that I reference later in this blog post.)

For instance, Crawford was involved in Lord Dunmore’s War. The Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh has an exhibit about this.

Let me tell you a little bit about how Colonel William Crawford died.

The American Revolutionary War ended in 1783. However, in the years before this, the settlers in colonial Pennsylvania and Ohio fought the British and they also fought assorted Native American communities. The settlers killed Native Americans, and the Native Americans killed settlers.

(The Heinz History Center, which was linked above, is an excellent resource about this historical period. The following is a very, very stripped down story about Simon Girty’s alleged role in the death of Colonel Crawford.)

During this time period, Simon Girty, a white guide who was raised by Native Americans, defected to the British and their Native American allies. Prior to the defection, Girty operated out of Fort Pitt as a “home base.” Girty’s defection to the British was a controversial event in Western Pennsylvania. Girty fled to Ohio. I invite you to read the resources available through the Heinz History Center for a more in-depth discussion about Simon Girty.

Then, in 1782, Crawford led the Crawford Expedition against Native American villages along the Sandusky River in Ohio. These Native Americans and their British allies in Detroit found out about the expedition. They ambushed Crawford and his men. These Native Americans and the British troops defeated Crawford and his militiamen.

A force of Lenape and Wyandot warriors captured Crawford. They tortured Crawford. They executed him by burning him on June 11, 1782.

Simon Girty was there, at William Crawford’s execution.

In fact, witnesses alleged that Girty “egged on” Crawford’s captors as they tortured him. Witnesses even alleged that Crawford begged Girty to shoot him as he burned alive, and that Girty laughed at Crawford.

Girty denied that he encouraged the warriors who tortured Crawford.

Girty settled in Detroit, among the British. Years later, Detroit became part of the United States and Girty fled to Canada. At least one internet source listed Girty as a Canadian historical figure. I learned that Girty’s name appears on an Ontario memorial for “Loyalists” (to the British Crown).

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) dedicated at least two plaques in Girty’s memory. (To my knowledge, the PHMC dedicated one plaque to Girty in Pittsburgh (near the Waterfront shopping district) and another plaque to Girty along the Susquehanna River in the Harrisburg area. This second plaque commemorates Girty’s birthplace in Perry County.

Now, Hannastown was the first county seat of Westmoreland County, PA. I read that the town lost a significant portion of its able-bodied fighting men in the Crawford Expedition. On July 13, 1782, Seneca warrior Guyasuta and his men burned Hannastown and its crops. Greensburg became the county seat after this.

If you want to read historical fiction in which William Crawford and Simon Girty appear together, then I suggest “The Day Must Dawn” by Agnes Sligh Turnbull.

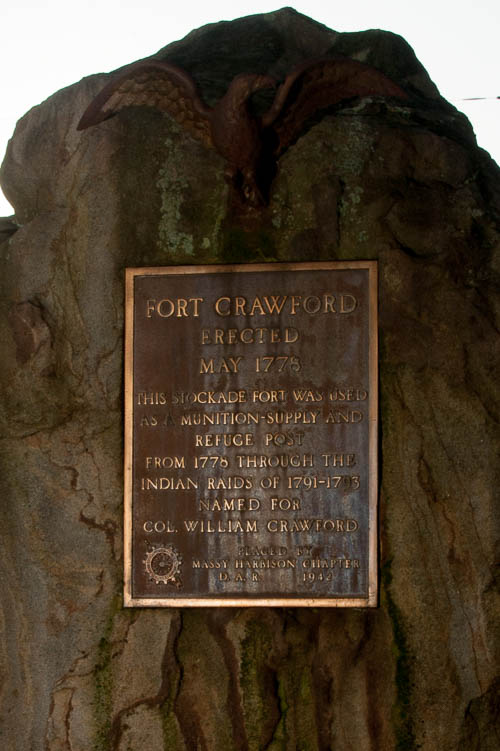

(Postscript, 09/16/20: Per the photo at the top of this blog post, there is a monument to Fort Crawford and to Colonel William Crawford in Parnassus in New Kensington. The Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated it in 1943.)

Wow! I found this very interesting! I love history! The good and the bad! Keep up the great work!

Thanks for the kind words, Janet!

Facinating. It has come to my attention that this monster is a relative through my Maternal Grandmother. My sympathies lie with the native Americans who sought revenge for his brutality. He probably died still believing he was of the superior race. Fool.

Thank you for reading my blog and commenting, Sandra! I, personally, didn’t learn about Crawford until I was an adult. My grandma used to bring up Simon Girty when I was a kid. Later on, I moved to a neighborhood that included a landmark to Crawford and I learned about Crawford. I was surprised to learn that Girty was reportedly present at Crawford’s death. I was even more surprised later on to learn that a Columbus ghost story centers around Crawford and the men that he commanded. To be honest, though, I don’t think that I would have paid any attention to William Crawford’s place in history were it not for the DAR historical marker that stands in my current neighborhood.

To be perfectly honest, I am myself the direct descendant of an American officer of the Revolutionary War. I am curious about this family history, but I am also nervous about uncovering too much information about this.

I am a descendant of Crawford, but this truth makes a lot of sense with my understanding of my family’s history. Thank you for publishing

Thanks for commenting, Anonymous. Unfortunately, most of what I know about this is from what I’ve read in historical fiction and on Wikipedia, the website for the Heinz History Center, and heard on the folklore podcast listed above. I find this bit of history fascinating, though.

I recently found out that I am also a descendant of him. I’m curious what else you have found in his lineage.

William Crawford is my 4th Great Grandfather. It’s called KARMA!

Mary Ann, if you are DNA related to William Crawford could you contact me privately? I am researching my genealogy. I have done my DNA through Ancestry and 23 and me. My nephew has done his through familytreedna.com They have a Crawford project going. So far, they don’t have anyone who is a descendant of William. darlenelliott@msn.com

Hello. I just read this article about Col. Crawford, and would like to offer a contrary opinion, if I may. He was indeed at the Salt Lick event you discuss, but it is not described in my many history books as a massacre. If fact, it is seldom covered as it was such a minor skirmish. In Col. Crawfords letter to G. Washington immediately after, he notes 6 Indians were killed, several wounded, 14 prisoners captured and 2 white prisoners freed. I think the salt lick story was confused with the Gnadenhutten massacre, which Col. Crawford was not present at and is on record as saying it was a travesty. For his ancestors sake, a correction, after your own research of course, would be most appreciated I’m sure. All the best…

Thank you for your interest in my blog post. I appreciate your insight into the subject. I edited the blog post to clarify that Colonel Crawford’s legacy is controversial, as is Simon Girty’s, but that the Heinz History Center is an excellent source of historical information.

I have never been to Columbus, and thus I have never been on the actual ghost tour that recounted the version of events at Salt Lick in present-day Columbus. My knowledge of the story told on the Columbus ghost tour is limited to what was communicated about it on the referenced podcast. I have no knowledge of the tour operator’s research methods.